It's not a lighthouse, it's a radar.

INFO

One of my current projects at the ANU School of Cybernetics is to develop tools & procedures for futuring. This post is an attempt to get my head around how these things fit together (spoiler: they do!).

Futures

Futures/futuring[1] is a thing—see Smith and Ashby for a practical guide or Powers for a more critical history and review. It’s the idea and practice of futuring as a verb, and this video from the Institute for the Future is a good articulation of the “pitch”:

Just so I’m clear up-front: I think that futuring is a genuinely useful tool in the toolbelt of any individual or organisation trying to figure out what success looks like and how to achieve it.

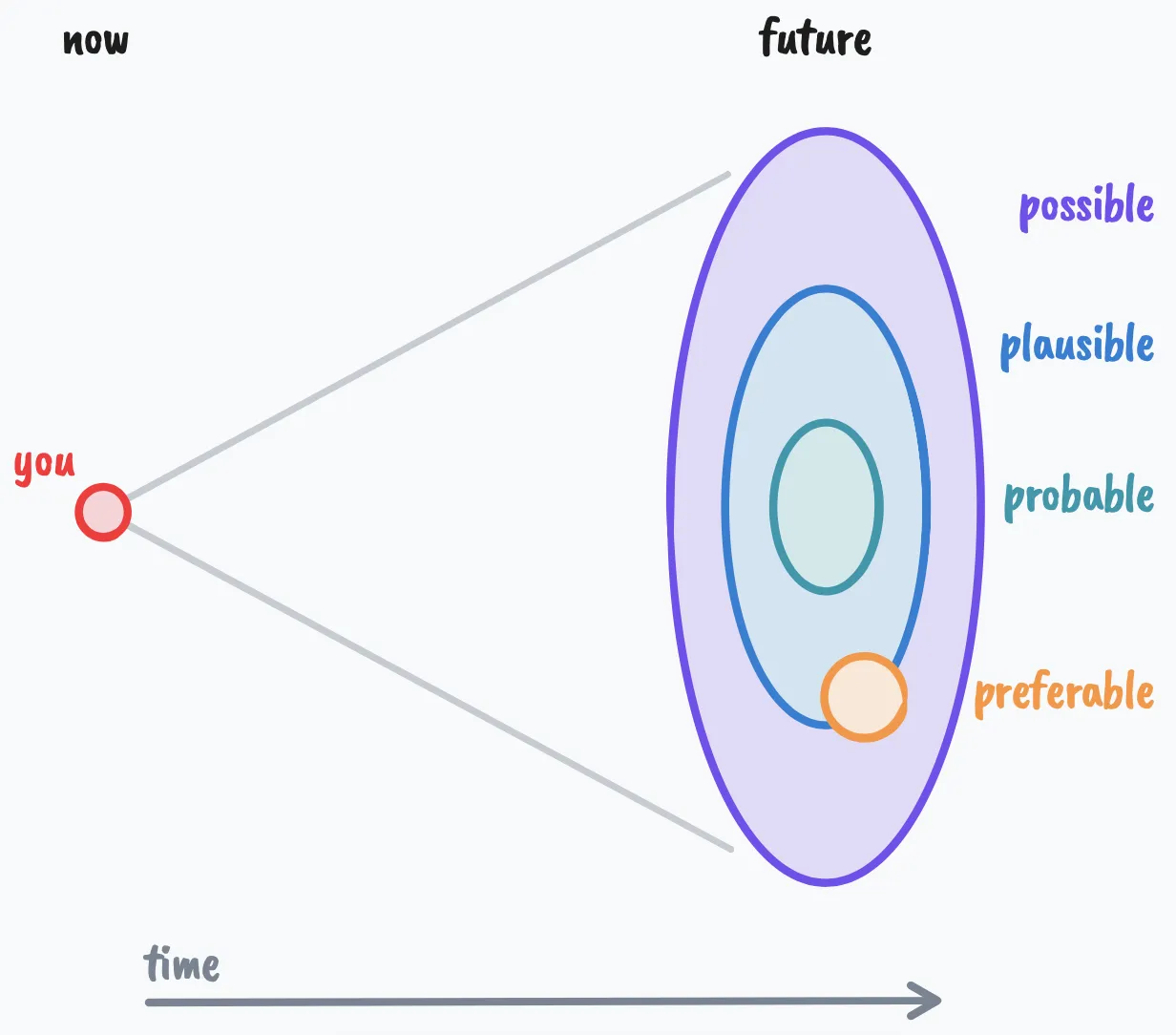

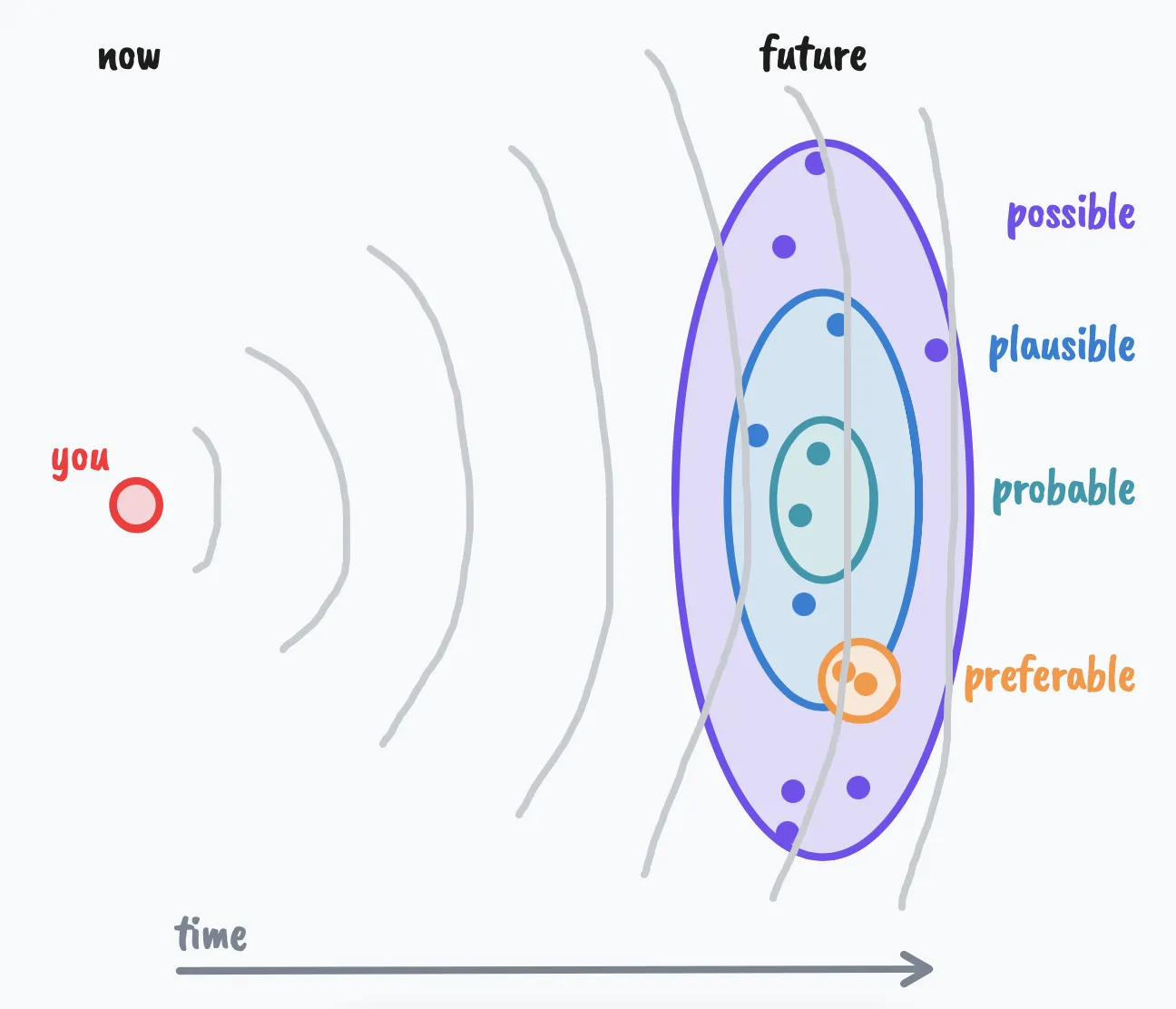

One diagram which is often used in futuring is the futures cone, which helps visualise the relationship between the now and the different potential futures which might eventuate.

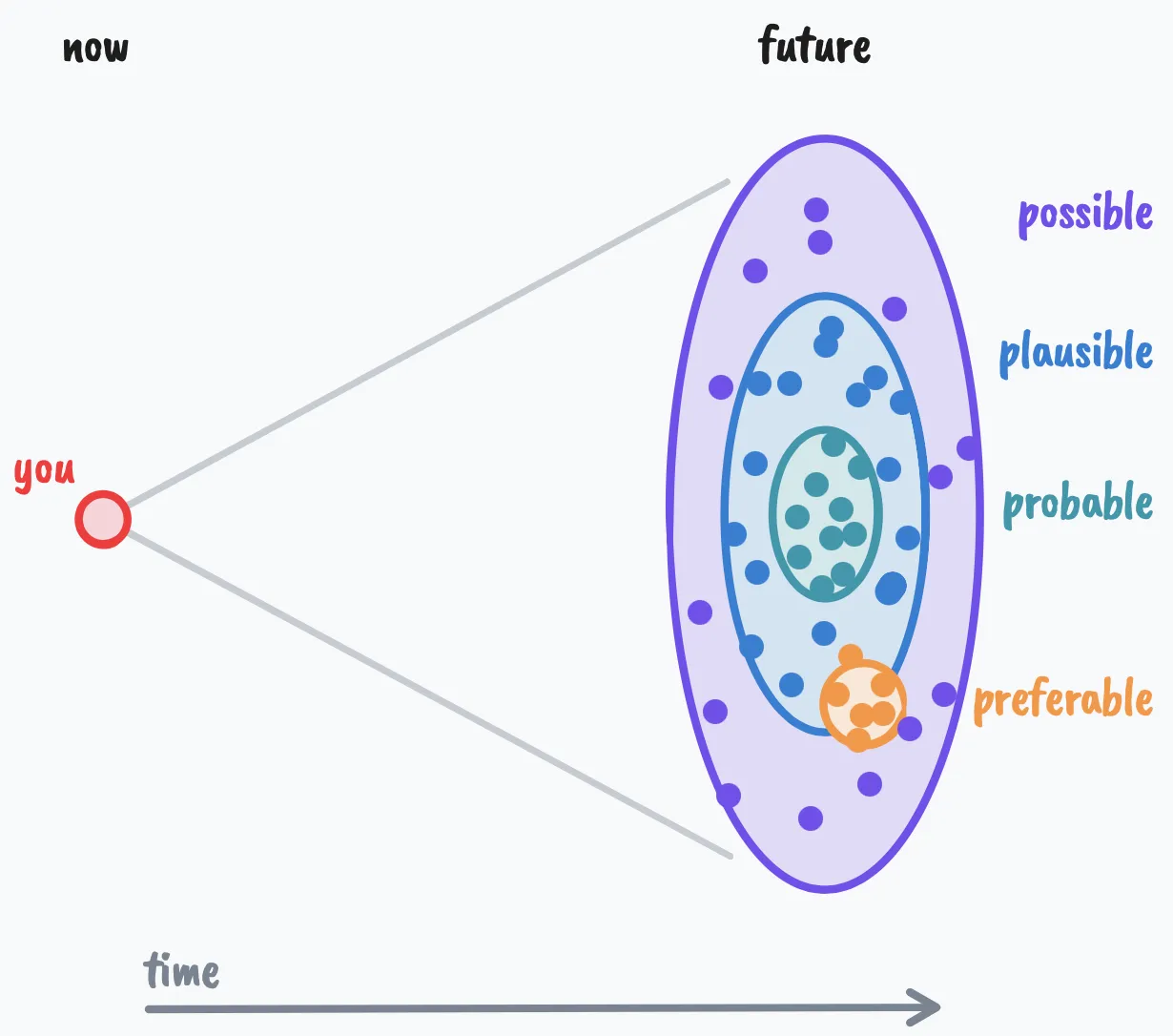

This diagram is just a visual aid—the future doesn’t really exist as a series of concentric discs of soothing colours—but it helps to anchor discussions we might have and predictions we might make about the future. In this sense, any prediction or “vision” of the future is a single point in the futures cone, and exactly where it falls in the space of possible, plausible, probable, or preferable futures is part of the discussion. Think about it as monte carlo of the future:

One thing to note here is that futuring is not about predicting the future. In many ways it makes one less certain about the future; futuring requires a healthy dose of epistemic humility, but that’s ok. It’s hard to expect the unexpected and predict the unpredictable, so these sampled points (potential futures) are really just a way of thinking about the current state of the world, and especially how we might act and position ourselves in the world now to make the most of future opportunities and steer towards the more desirable potential futures.

Cybernetics

Stafford Beer tells a joke about defining cybernetics in an address he gave at the University of Valladolid:

…it concerns three men who are about to be executed. The prison governor calls them to his office, and explains that each will be granted a last request. The first one confesses that he has led a sinful life, and would like to see a priest. The governor says he thinks he can arrange that. And the second man? The second man explains that he is a professor of cybernetics. His last request is to deliver a final and definitive answer to the question: what is cybernetics? The governor accedes to this request also. And the third man? Well, he is a doctoral student of the professor—his request is to be executed second.

It’s a great joke, grounded in a deep truth. One way to define cybernetic systems is as systems with (i) a purpose/goal and (ii) a mechanism for steering towards[2] said purpose. In some cases there’s a defined end state, where upon attaining said purpose victory is declared and the job is done. However in many cases what’s desirable is homeostasis, i.e. a system which can keep itself “in its happy place”, stable and resistant to peturbations.

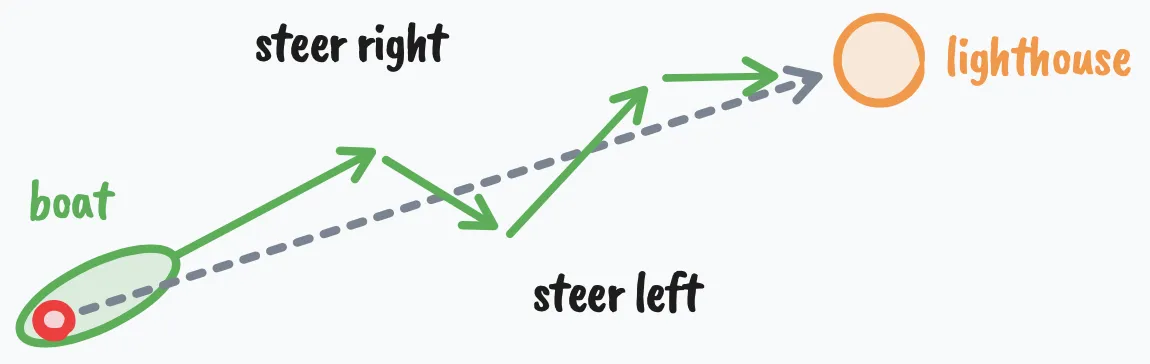

There are lots of potential illustrations of this idea, but one that many of my cybernetic forebears liked is the one of using a lighthouse to steer a ship. Here’s a nice explanation:

In ancient Greece, the Kubernetes > [navigator/helmsperson] was in charge of controlling the Grecian longships. The ships had to be steered through all kinds of unpredictable forces, including wind, waves, storms, currents, and tides. The Greeks found that they could ignore all of these and control the ship via a small tiller connected to the ship’s larger rudder just by pointing the tiller toward a fixed object in the distance, such as a lighthouse, and making adjustments in real-time.

There’s a YouTube “What is cybernetics?” video which includes a diagram like this:

It’s not the particular position of the tiller at any one time that’s important, is the way that the navigator watches the lighthouse and moves the tiller in response (as the ship is affected by currents & winds). If the ship’s bow is pointing to one side of the lighthouse, then adjust the tiller in the opposite direction until it does. If you keep up that simple procedure, you’ll get there in the end, and with your ship in one piece.

It’s the navigator’s continued monitoring of the difference between the purpose/goal (as indicated by the lighthouse) and the current state (as indicated by the where the bow is pointing) which matters. Once you know how to respond to that difference, by steering in the opposite direction of that difference, then you’ve got a simple and reliable procedure for successful sailing.

Here’s the key point: cybernetic systems don’t work by planning out a complex, go-to-whoa list of actions to take and then mindlessly following them. Instead they use a simpler process involving feedback: do a thing, looking/listening/sense what happened, compare the new state of the world with the goal, and then do another thing… and so on[3].

Here’s another example of a feedback-powered system. The development of radar in WWII was deeply connected to the birth of cybernetics (as detailed by Thomas Rid in Rise of the Machines Chapter 1). Take it away, Wikipedia:

A radar system consists of a transmitter producing electromagnetic waves in the radio or microwaves domain, a transmitting antenna, a receiving antenna (often the same antenna is used for transmitting and receiving) and a receiver and processor to determine properties of the object(s). Radio waves (pulsed or continuous) from the transmitter reflect off the object and return to the receiver, giving information about the object’s location and speed.

The radar sends out the pulses, which bounce (reflect) off the environment—and these these reflections are sufficient (with some tricky maths) to figure out what the environment looks like. Often there’s some sort of visual representation of the results, like the classic “beeping dots on concentric circles” radar sweep interface you’ll know from the movies.

The radar example is different from the ship steering one in that lighthouses don’t really move/change (although the currents in the water & other environmental factors do… hence the need for the feedback-powered steering procedure). Using the radar properly requires sending an ongoing series of pulses, because they each give an indication of what the environment looked like when the pulses were reflected, but to track moving objects you need to monitor the dots over time to see how the environment changes.

Cybernetic futures

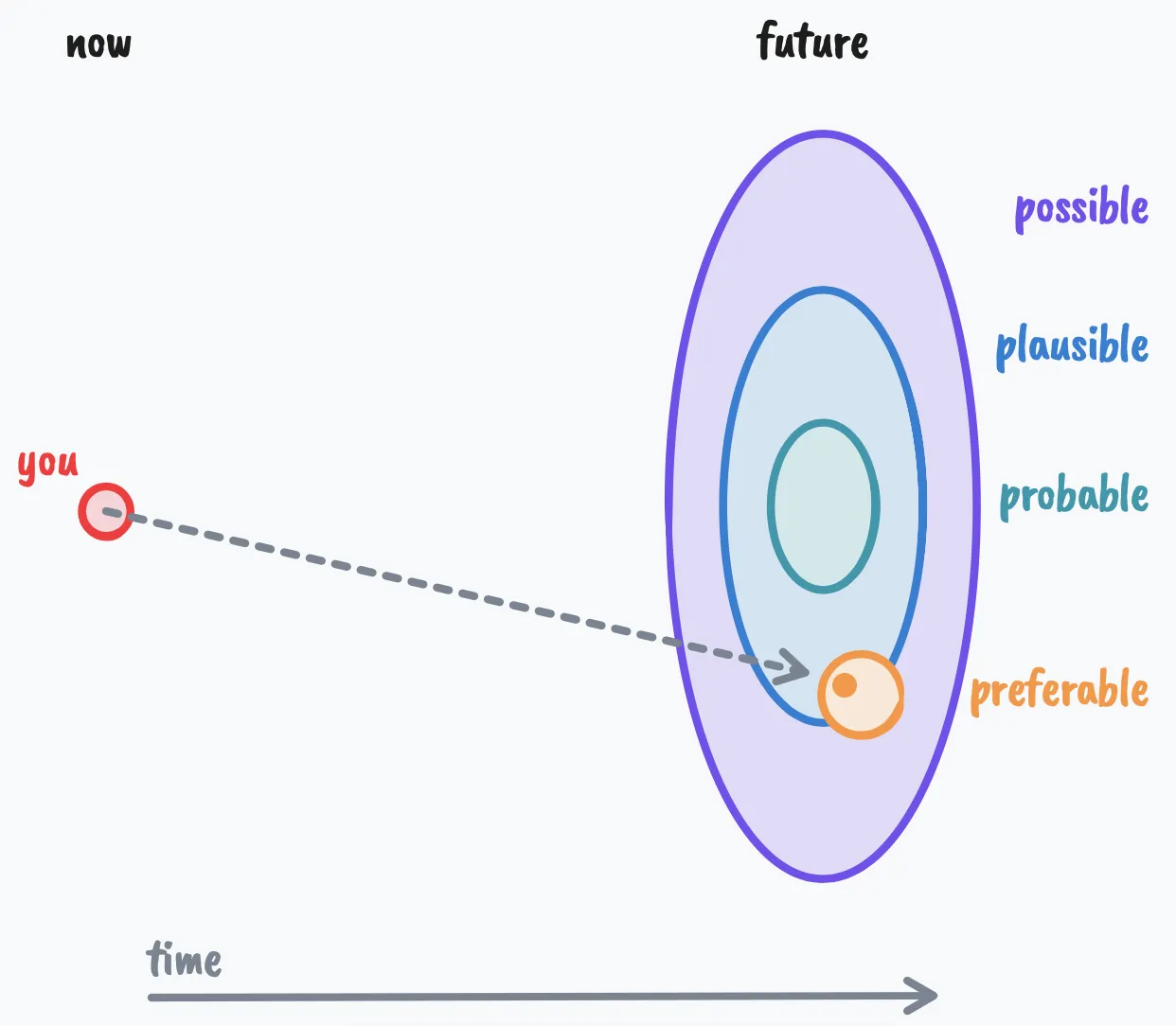

Returning to futuring; each future scenario you can imagine (regardless of where it falls in the futures cone) is a way of projecting a potential “end state”. That end state doesn’t have to be desirable—many potential futures aren’t—but it gives a “concrete” thing against which to compare your current state to inform your current actions. Even the more mundane acts of management and oversight—strategy, tactics, contingency planning—when done well they all involve articulating goals and thinking about ways to bring them about. There’s clearly an echo of the “steering systems” thing here.

However, one pitfall of that sort of mental picture of the future is that futuring looks like a three step process:

- come up with (sample) a bunch of potential futures from the futures cone (the points in the diagram above)

- pick one of the potential futures you like the most (from the preferable area of the futures cone)

- steer towards[4] it like a lighthouse (whatever that looks like)

That’s an unhelpful picture of what futuring is because it implies that the potential future you’re steering towards is solid & stationary, but that’s just not how potential futures work. Instead, I think that futuring works best when it’s more like a radar:

- come up with (sample) a bunch of potential futures from the futures cone (send out radar pulses)

- look for their reflections in the present

- analyse these reflections to decide how to act

- goto step 1 (because things have now changed)

As well as giving a different mental model of what futuring is and isn’t, I think there are two implications of this switch in perspective.

Just like a ship drifts on the currents, our orientation to these potential futures is constantly changing as we & others act in the present—we’re agents; we have agency. So we need to constantly re-examine our orientation towards these multiple futures and reorient ourselves as a result. That’s a “radar-like” model of futuring. Cybernetics doesn’t provide a “once you measure & model all the things you can predict the future” silver bullet (although it’s not like some folks haven’t tried and failed), but rather it’s a commitment to using a simple “sense-analyze-act” feedback loop to keep the system on track.

Don’t be fooled by the simplicity of the steering procedure in the ship/lighthouse example; the radar example shows that making sense of the feedback from the environment can require non-trivial analysis before it’s useful.

To close, I want to stress that I’m not saying anything remotely new here about the connection between futuring and cybernetics—they’re very often seen & discussed together. William Gibson, award-winning sci-fi novelist and sometime futurist was steeped in cybernetic lore when he coined the term “cyberspace”. My boss Genevieve Bell AO, director of the ANU School of Cybernetics, has thought deeply and written persuasively and generally projected big futuring energy for pretty much her whole career.

Footnotes

or foresight, or forecasting… there are a few terms which are used relatively interchangeably ↩︎

The system’s purpose can also be stated negatively, e.g. avoiding pain. So towards/away from are equally valid when talking about purpose. ↩︎

If that definition sounds all-encompassing, you’re not the first person to notice that. Cybernetics isn’t shy about claiming all things as within its purview—Wiener was an ersatz theologian. ↩︎

Yeah, I know, you don’t steer towards the lighthouse exactly—they just show you where the rocks and reefs are. Don’t @ me. ↩︎