11 Nov '21

Livecoder-in-the-club as a system

understanding and intervening in complex flows of software, music and humans

Here in the School of Cybernetics we are building our capability in cybernetics—its histories and possibilities—and working out how each of us will contribute to the new cybernetics for the 21st Century.

This blog post, written for a general audience, is part of a content development sprint, written in reponse to the task of developing a short (1000 words) persuasive argument about the role and value of cybernetics as an approach to shape futures through and with technology.

If you follow this blog, you’ll know that I’m a livecoder. I code (i.e. write computer programs) to make music in a club setting, with an audience that just wants to dance and have a good time1. If you’ve never seen it before, here’s a 10min video of my collaborator Ushini Attanayake and I.

Between the code, the thumping music, the dancing humans, and all the other glorious complexities of live entertainment, there’s certainly a lot of different stuff going on. You might find watching a livecoder in action to be entertaining, or impressive, or bewildering, or all of the above. Most of all, when you see/attend a livecoding gig for the first time, I bet that your initial feeling is one of what is going on?

In this post I’m going to use some ideas from cybernetics to try and help you make sense of a livecoder performing in a club, in part to help you understand for what it feels like I’m doing when I do it. From there I want to think about ways to make livecoding even better, that is, to figure out put on a better show for the adoring crowds.

Livecoder-in-the-club as a system

Cybernetics is all about the looking at and reasoning about systems with goals, interacting with and connected to their environment via perception/action feedback loops. These sorts of systems exist at all sorts of different scales (big/small, fast/slow, old/new, cheap/expensive, etc.) and they’re fractal in nature—it doesn’t matter what level of “magnification” you look at, each component of a system is itself a system of interacting components, and each system is itself a component interacting in a larger system. But since that’s all pretty abstract, let’s return to the example of the livecoder-in-the-club. This is written in the first person, but other livecoders may have similar understandings of their own livecoder-in-the-club practice.

-

I start with a full tank of brain juice which allows me to work on tricky coding problems. But it’s mentally taxing. When I’m happy, rested & in the zone, I feel like I’ve got a full tank, but writing code takes mental energy, and so writing the code in the performance drains my brain juice until I’m cooked, and then I can’t write any more code (or at least will write bad/buggy code) until I recharge.

-

To write the code I tap my fingers on the keys of my keyboard. I use a specialised program for this (i.e. I don’t write it in MS Word) which has a bunch of features to help, like different colours for the different parts of the code (e.g. functions vs variable vs numerical parameter values), and auto-completion, and inline documentation/help about the particular bit of code that I’m working on. This code is also projected onto a big screen in the club so that the dancers can look at it (or not).

-

As the code runs, it generates music. Different parts of the code are responsible for different parts of the music, and I try and give the functions & variables in my code human-readable names (like

piano) so that the correspondence between the code and the music is clear-ish. The music will only be generated if the code is running nicely (i.e. without bugs/errors) and is hooked up to the PA system in the club. If I crash the program (or if someone unplugs the PA) then the music will stop. -

The people in the club—people dancing, people chilling at the bar, people watching the code on the screen—are collectively having an experience which (hopefully) is giving them good vibes. Obviously this is a huge oversimplification, and the extent to which any individual is enjoying themselves (and therefore contributing positively to the amount of good vibes in the room) depends on all sorts of things. But, in a real sense, the creation of good vibes in the room is the goal of the live coder—or at least it’s my goal when I perform in this situtation. So I (like any performer) feed off the good vibes, replenishing (to some extent) my brain juice.

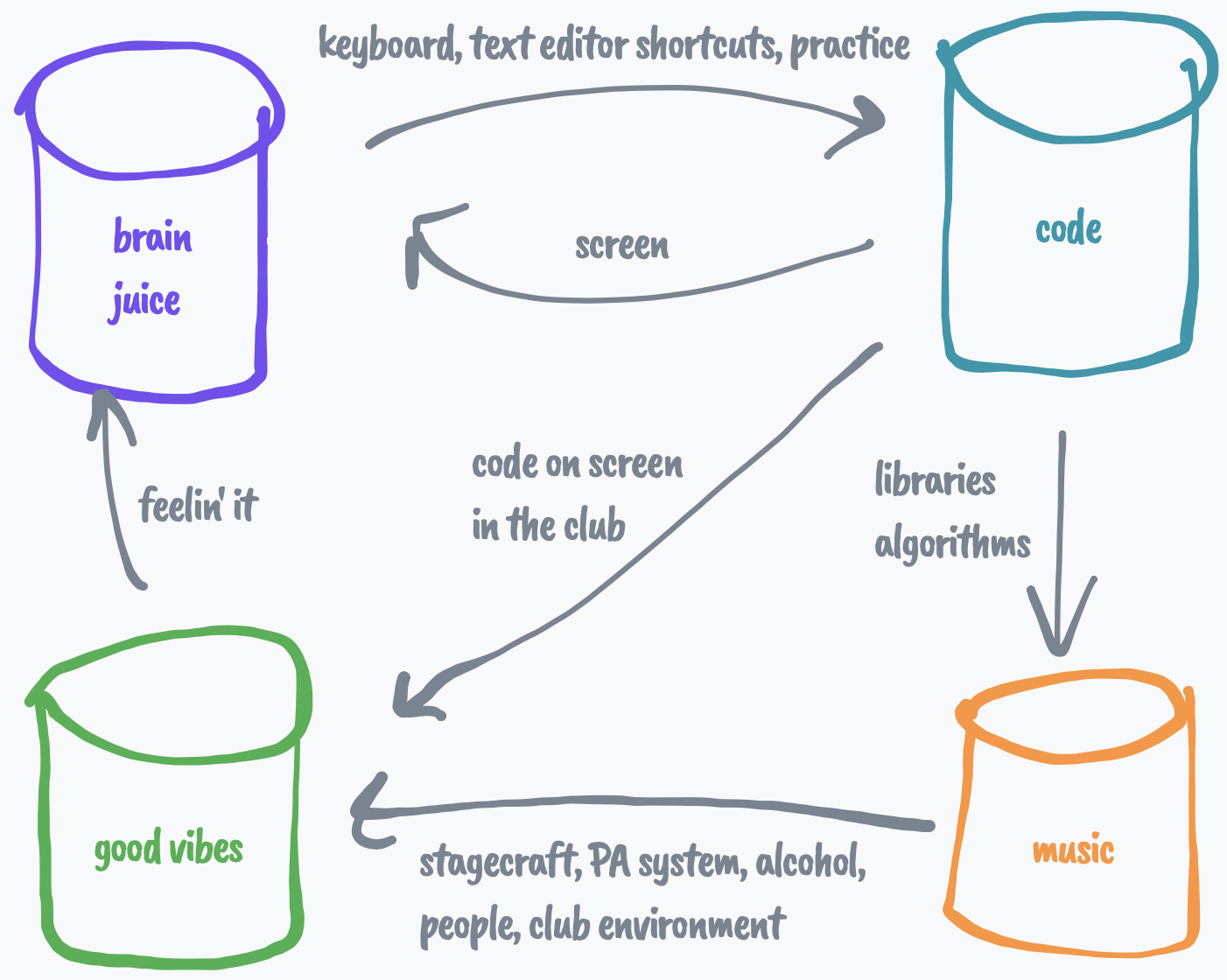

It’s a bit clearer to see in a picture:

So, clearly,

a livecoder is a machine for turning brain juice into good vibes (via code and music)

which is a nice way to think about it, and actually is a relatively accurate picture of what I feel is going on when I’m performing.

How does cybernetics help us understand and improve this system?

In this account of livecoding-in-the-club, there are a few things worth noticing:

-

there are different “stocks” (reservoirs of brain juice, code, music and good vibes)

-

there are various flows between those stocks, and in both directions (e.g. I turn brain juice into code by typing at my keyboard, but I also receive information about what the code looks like from my laptop screen, via my eyes)

-

there’s a goal: to put on a good show for the audience to enjoy (to increase the stock of good vibes in the room)

-

the system includes closed loops, and so is capable of feedback

A key principle of cybernetics is that the structure of the system—what the parts are, and how they relate to one another—determines the behaviour of the system. But anyone can sketch out a (highly contestable) jumble of blobs and arrows to describe whatever thing they’re interested in. What do we gain from seeing things in this way?

This is where another key idea—and person—in cybernetics/systems thinking comes in: Donella Meadows’2 Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. The key idea is this: once you’ve mapped out your system, you need to know where the most effective “intervention points” to try and implement change? If you’re going to expend energy to make things better, where should you focus that energy to get the most leverage?

In the livecoder-in-the-club system, to make changes to the system in service of the the goal (as stated above) of creating maximum good vibes. One obvious solution is to start the gig with a bigger reservoir of brain juice (either by having a good night’s sleep, popping an adderall, or whatever). Or it could be to start with a larger code reservoir by starting with a bunch of code pre-written3.

However, Meadows’ rules for leverage also suggest that some interventions provide more leverage than others4. For example, changing the flow rates (leverage point #10) is likely to have more impact than just changing the sizes of the stocks/buffers (leverage point #11). This implies that changing the rate at which I turn brain juice into code (perhaps having a nicer keyboard, perhaps having better code auto-completion support, or perhaps just good-ol’ practice to improve my coding skills) is likely to be more impactful than starting with a bigger store of brain juice (so, thankfully, there’s no need to buy shady adderall on the dark web). Will Larson (who has been a software engineering leader at Calm, Stripe, Uber, and Digg) has some interesting ideas on systems thinking as applied to software development that I’m keen to think more about as well.

For even greater leverage, there are interventions which are related to restructuring the system itself, for example adding new information flows (leverage point #6). The dancers can already see the code, but what if I was hooked up to a live EEG so they could see the current state of my brain juice?5. And even higher up (in terms of leverage) is changing the goals of the system itself (leverage point #3). Why do people come to a club to dance and have good vibes? What if their goal was different?

Now, the thing about leverage is that it doesn’t guarantee good or bad outcomes, it just means you for a small amount of input you see a large effect in the output. Figuring out where to intervene in the livecoder-in-the-club system is one thing, figuring out how to intervene so that the changes are positive is a deep challenge. Leverage means that when things go well they go really well, but the opposite is also true (e.g. with margin calls in a bear market). I feel like this is an especially apposite point for programmers, because the cheap leverage afforded by software is catnip for programmers, but presents some real dangers. (as as Maciej Cegłowski puts so eloquently).

So what’s the point?

Obviously the livecoder-in-the-club system described above is an oversimplification; it makes certain things easy to see but renders other things invisible, and every aspect of both the components (the things it talks about) and their relationships (the connections between them) is contestable. But that’s one of the benefits by laying things out like this—we can at least see the things that we’re explicitly considering, and we may well need to add new things to the model for consideration (and examine all the new connections and potential feedback loops those new things create).

My main goal here is really just to provide a worked example of how ideas from cybernetics and systems thinking can help us move beyond just describing things to figuring out where to place our energies to effect change—where we’ll get the most leverage. Being the best livecoder I can be is a lifetime goal, just like any other instrumental or artistic practice. I’m keen to keep using the tools of cybernetics to push in that direction, and bring the assemblage of dancing bodies of the livecoder-in-the-club system with me for the ride :)

Appendix: Meadows’ 12 Places to Intervene in a System

Note: these are taken straight from the Donella Meadows foundation website.

(lower numbers = less effective, higher numbers = more effective)

- Constants, parameters, numbers (such as subsidies, taxes, standards).

- The sizes of buffers and other stabilizing stocks, relative to their flows.

- The structure of material stocks and flows (such as transport networks, population age structures).

- The lengths of delays, relative to the rate of system change.

- The strength of negative feedback loops, relative to the impacts they are trying to correct against.

- The gain around driving positive feedback loops.

- The structure of information flows (who does and does not have access to information).

- The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishments, constraints).

- The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.

- The goals of the system.

- The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.

- The power to transcend paradigms.

Footnotes

-

It’s a pretty niche activity, but there’s an international community of us, and if you’re interested then you can follow me on bluesky to hear about upcoming gigs. ↩

-

Donella Meadows tended to prefer terms like “systems thinking” and “systems change” rather than using the term “cybernetics” directly, but she certainly was involved with some of the key people & events in the cybernetics story, and her work is highly relevant to cybernetic ideas. Plus, Google Books categorises her work under Computers > Cybernetics, and you know the Big G is never wrong about that stuff. ↩

-

This is actually a subtle point in livecoding. I (along with some other livecoders) am committed to starting each gig “from scratch” with a blank code page. However, I’ve written a lot of library code ahead of time to provide me with nice abstractions for making music with code, and I use that (hidden—not on the screen) from the very first line of code that I write. Thinking about the livecoder-in-the-club system one question that I’m pondering is whether that library code constitutes a larger stock of code, or whether it’s a restructuring (an increase) of the flow rate from code into music, or both.

To make things even more complicated, and there’s kindof a blurry line between where the code ends and the music begins in livecoding (i.e. there’s the code you see on the screen, which is the code that I’m writing & executing “live”, but there’s also a bunch of pre-written code in my operating system’s audio plumbing just to get the music to come out of the speakers properly). ↩

-

There’s not enough room in this blog post for a full “systems change analysis” of the livecoder-in-the-club system according to all 12 leverage points, but if you’re interested I do recommend you check out that article as a starting point. ↩

-

Coming up with a reliable, portable EEG machine which can measure a useful biometric signal which corresponds to an individual’s perceived current level of brain juice is beyond the scope of this blog post. ↩